I have added many features to the space project over the last few months. But one feature that I have been looking forward to adding for a long time has finally come to fruition. It’s a feature that adds a small touch of life to the game and is useful for countless dynamic graphics effects. By now you probably have guessed it (not to mention the blog title)… Particles!

Set the controls for the heart of the sun!

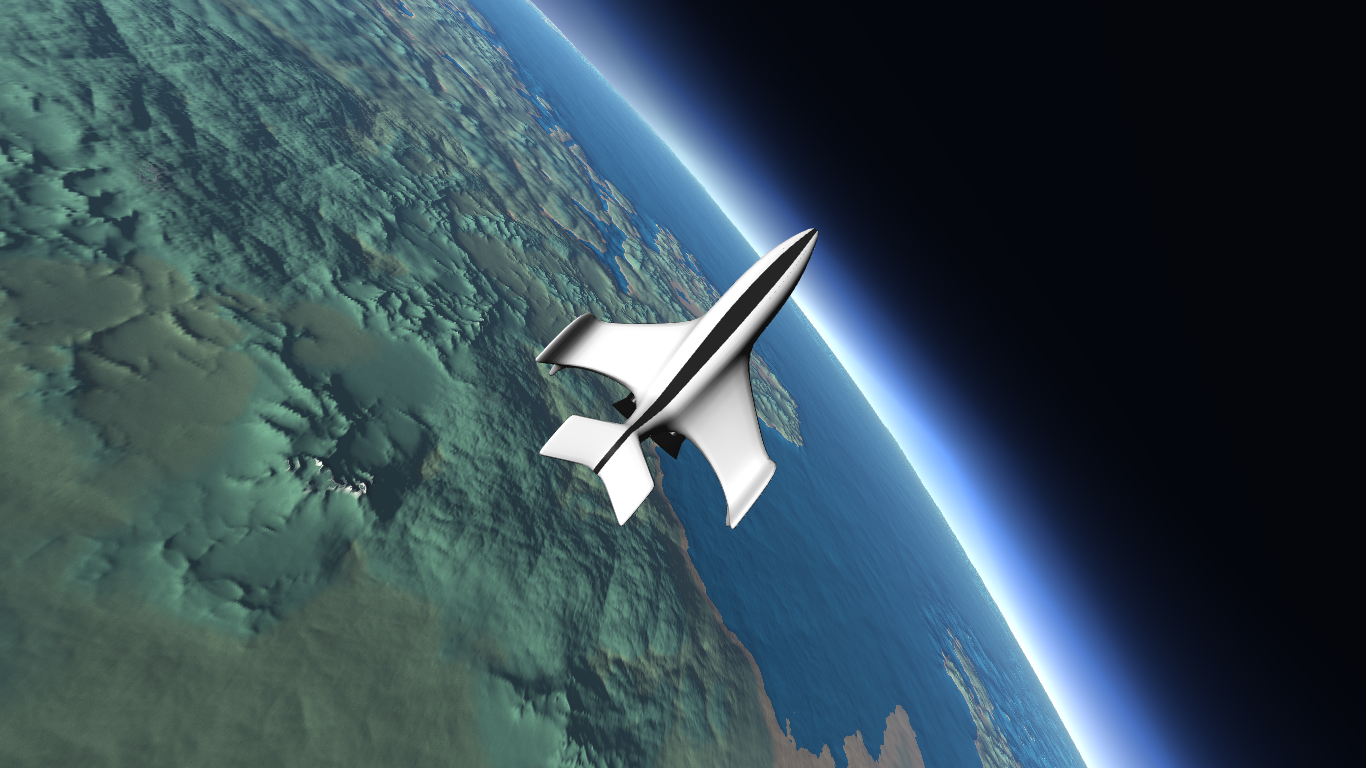

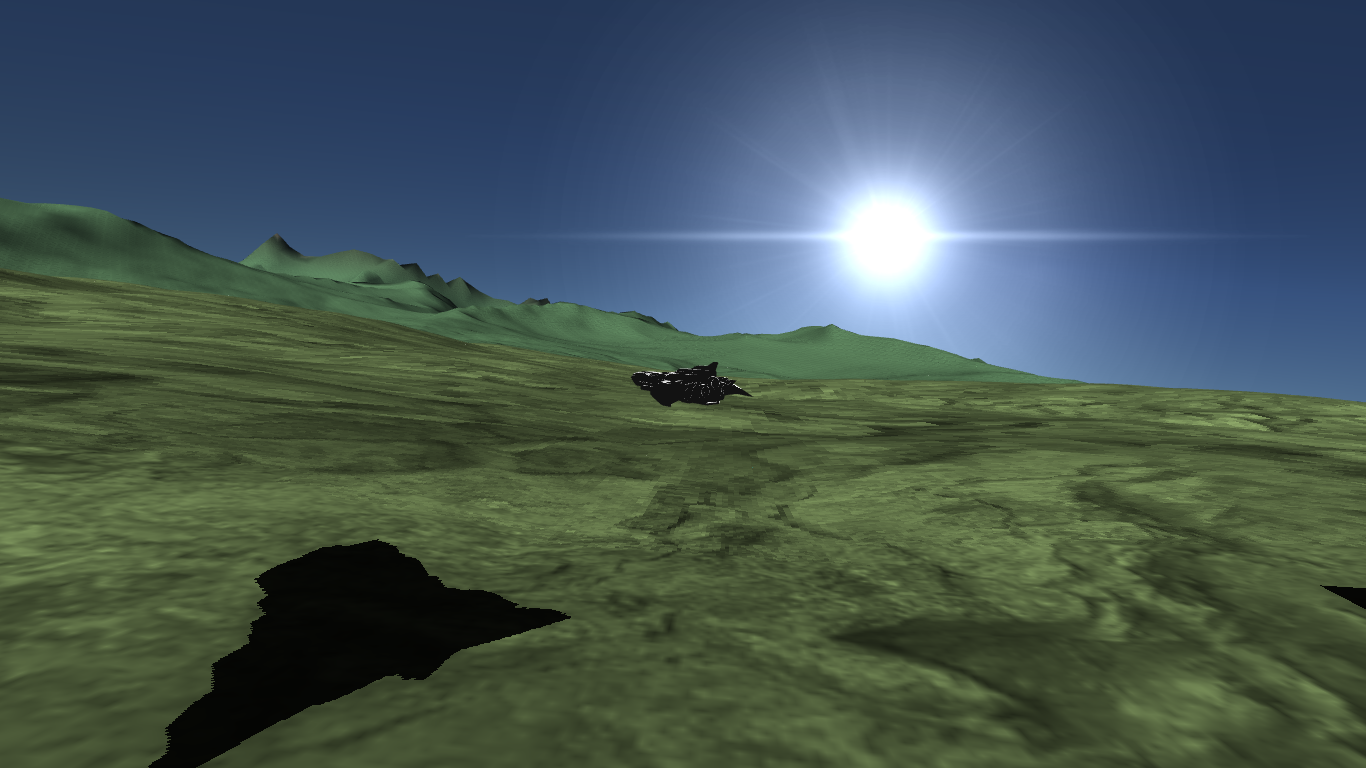

The space project’s Particle System faces many of the same precision issues that have made conventional approaches more difficult. These particles must be able to be emitted at very high relative speeds, and in many different reference frames and coordinate systems. By making use of double precision on the CPU-side, and emulated double precision on the GPU-side, I am able to accurately render many billboard particles at a wide range of velocities and distances throughout the entire Star System.

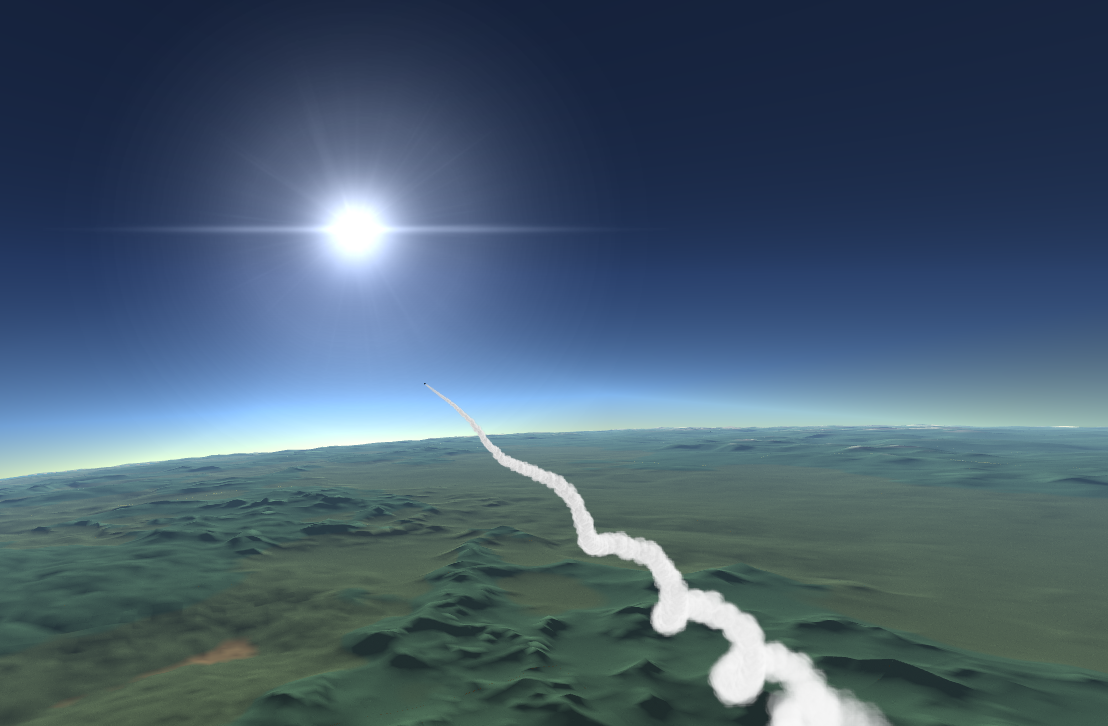

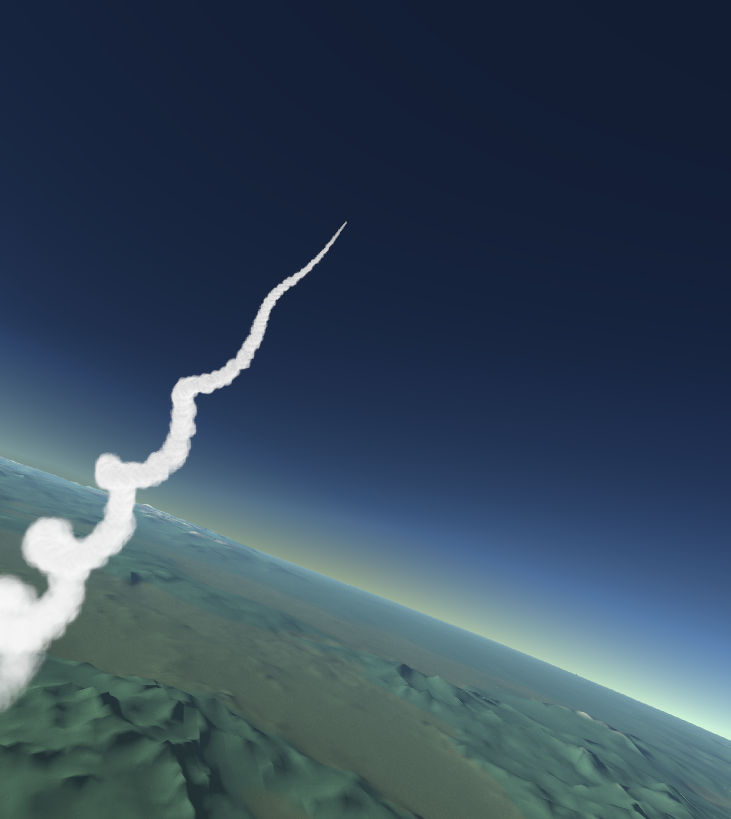

The Particle System itself is based on a pool (underlying deque) of IDs that point to Particle objects in a constant-size array. Active particles are moved from the pool to a list where they are updated every frame. An active particle has a life cycle that is directly related to its current “alive time,” which measures how long in seconds the particle has been alive. During this life cycle, particle parameters can be adjusted based on functions or simple interactions to create interesting graphical effects. Once a particle has reached its end-of-life, it is transferred back into the pool where it can flag that it is available for use again.

On the graphical side of the house, the particle position and parameters are stored in a dynamic Vertex Buffer Object (VBO) which is updated after any change is made. Like other graphical objects in the game, positions are assumed to be relative to eye (or camera) to conserve precision close to the viewpoint at the expense of precision far from it. This results in a very stable simulation with minimal apparent jitter. The Particles are sorted by the square of their relative to eye position for correct alpha blending of translucent objects.

This is the most stable and efficient launch profile for this spacecraft.

The Particle System is far from compete and currently only supports smoke trails. However, the bulk of the implementation is out of the way. New Particle types can be rapidly added to support all kinds of graphical effects. But for now, what other than smoke does a space game need to support? Yeah, yeah, fire and… explosions of course! Stay tuned.